MANY Board Spotlight: Michael Galban, Historic Site Manager and Curator, Seneca Art & Culture Center, Ganondagan State Historic Site

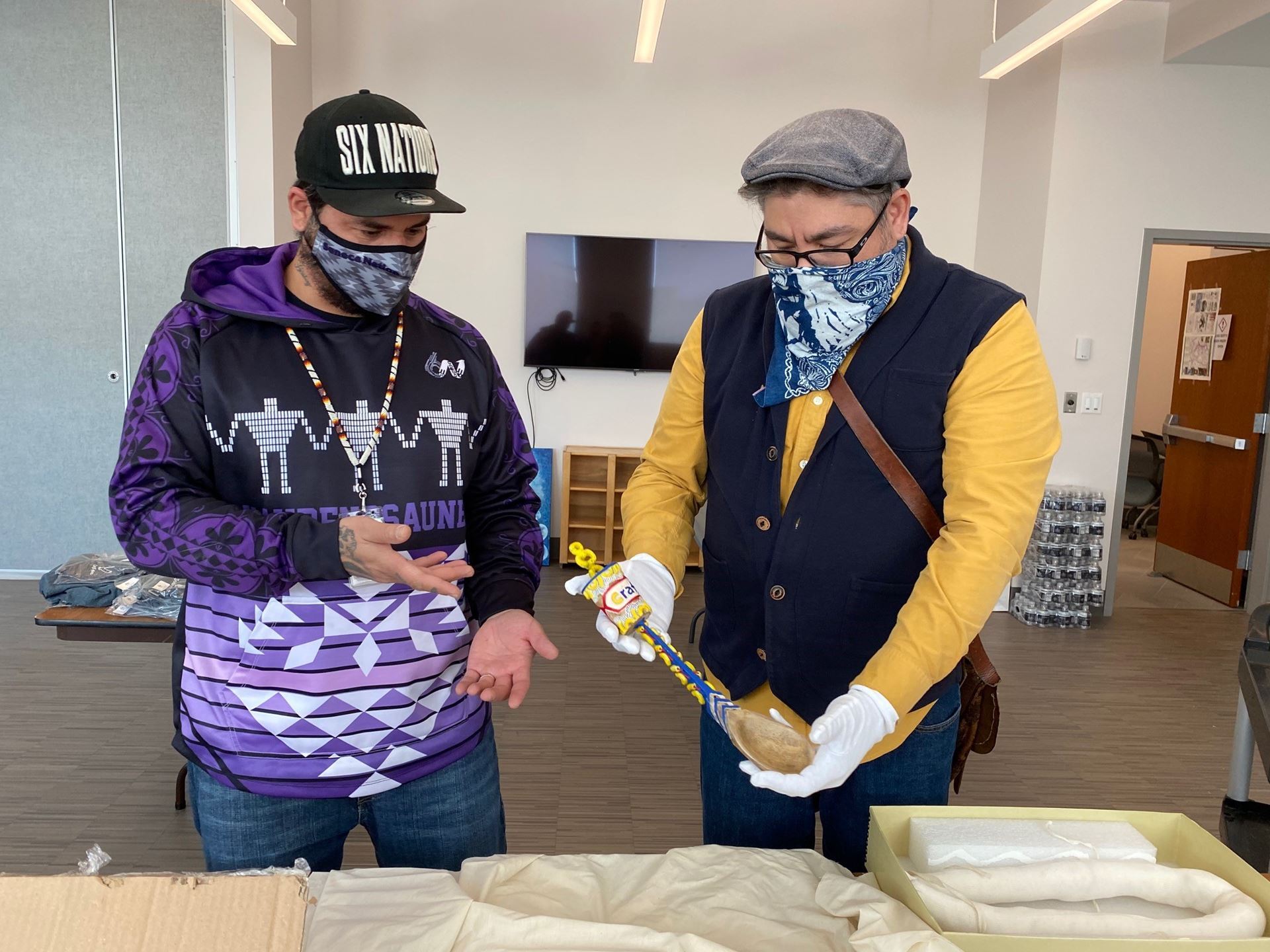

Michael Galban (right) picking up a 2020 Art piece purchased for the collection Hayden Haynes Seneca artist.

Michael Galban (right) picking up a 2020 Art piece purchased for the collection Hayden Haynes Seneca artist.

Michael Galban is the Historic Site Manager of Ganondagan State Historic Site and the curator of the Seneca Art & Culture Center. Ganondagan is a 17th-century Seneca town site and is nationally regarded as a center for Iroquoian history, and cultural and environmental preservation. His current research focuses on historic woodland arts, Indigenous/Colonial history, and lectures on the subject extensively. He sits on the board of directors of the Museum Association of New York (MANY), the editorial board of the New York History Journal, and is currently working in the Indigenous Working Group component of REV WAR 250th NY commission.

He recently curated the exhibit “Hodinöhsö:ni’ Women: From the Time of Creation” at the Seneca Art & Culture Center which is open through 2023. Michael is currently researching moose-hair false embroidery of the northeast as part of his Ph.D. work in the University of Rochester’s Visual and Cultural Studies program. Michael recently collaborated with the Museé du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac on the exhibit “Wampum – Les Perles de la Diplomatie” which opened this Spring and will travel to the Ganondagan in 2023 as the exhibit “WAMPUM/OTGO:Ä”.

What other jobs have you had in the museum field? Can you tell us about your journey to get to your current role?

I’ve worked at Ganondagan since 1991. Before that, I was more or less a young kid really so I honestly didn't have any other museum jobs. I worked at the Helmer Nature Center for a while that was related in terms of interpretation, but really nothing else in the museum field other than Ganondagan. At the nature center, I gave tours and worked in the nature camp. They had a wildlife rehabilitation so I was learning that too. It helped me understand how to communicate with the public. When I started here I did a lot of things from mowing the lawns to community outreach. I think that I grew into the position more than was recruited into the museum.

I was in college at SUNY Geneseo and the site manager Peter Jemison knew of my family from being in the urban Native American community. He reached out to see if I wanted to work here and I took the job.

The job was not very specific, so it didn’t have a title or a defined role description. So I was doing maintenance and interpretation. The first week I was here I was asked to lead an ethnobotanical plant walk with a group of Haudenosaunee Elders –which was like being thrown right into the fire. I did it because my understanding of interpretation at the time was to share what you know, make it interesting, have a goal, and your audience will like it. The Elders liked my tour and were really receptive. For me as a young person, it was very encouraging.

It was pretty frightening because you feel unprepared maybe and I lacked the confidence of a seasoned interpreter. My undergraduate degree was in fine art. Of course, I had an art history component and anthropology minor and you know those are all well and good but don’t exactly prepare you for the position that I was in. And to be frank about it I didn’t take it very seriously because I didn’t expect to be here thirty-plus years later. It was not part of my life plan.

Would your 18-year-old self imagine that you would be where you are today?

I had a vague idea of what I wanted to do. My course of study was art and I imagined that I would be this well-known, accomplished Indian artist. That’s what I expected to be and that was my vision to produce art and do shows, and just live that artist life.

Can you tell us about where you grew up and what was it like to grow up there?

I moved around quite a bit with my family but when people say “where did you grow up?” what does that exactly mean? What is place? How does place impact you and your development and worldview?

The place that really had the greatest impact on me is when we lived in Reno, Nevada. I maybe only lived there for four years from when I was nine or ten until I was fourteen years old. But it had such a profound impact on me. It’s where I say I grew up even though before that I was in Rochester and then afterward we moved back to Rochester.

But those formative years when you’re an adolescent and you become conscious of all kinds of things, that occurred to me in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Why did this place have such a profound impact on you in your adolescent years?

When you look back and review things that happened to you and evaluate how things impacted you, for me it took place when I was in grade school.

I went to the school which served the Native people from the Reservation which was about a third of the student population and the rest of the students were from Reno of various backgrounds, but mostly white children. Even though I was a new student, I was immediately accepted by the Native kids and even learned that one of the kids was my cousin. It was really welcoming and an incredibly warm and accepting feeling. It was a beautiful experience to kind of find your family, find who you are, and find that kind of acceptance into your group, your people. But at the same time in parallel, I didn’t realize that we were not actually being taught.

We were situated in the back of the classroom against the wall with one or two rows of seats dividing us from the rest of the students in the class. We were just allowed to goof off, draw, and pass notes and not really pay attention because we weren’t really part of the class. When the marking period ended and my parents received my marks it was a shock to them. I am not a D student so my parents were wondering what was going on and as a ten-year-old, you don’t really have an answer to those questions. I remember going back to the classroom after school with my parents and sitting in front of her desk. The teacher was a young white woman, probably in her early twenties. My parents asked her why I was doing so poorly and she kind of sat there. I remember taking it all in and remembering what the teacher said to my parents “oh I thought he was just another Indian kid.” At that point my parents stood up, they didn’t say a word to the teacher but grabbed me and left. I never went back to that school. My parents went to the superintendent to bring the issue to them and somehow they got me to enroll in another suburban school.

It was very confusing when you find your place where you’re supposed to be as a kid and when you’re a kid acceptance is huge and then it’s being taken from you and you don’t understand why.

What was the first museum experience that you can remember?

Outside Reno, there is this little town called Virginia City. Virginia City historically is a mining town. You can visit and see the old western wooden buildings and a wooden promenade. It’s a touristy area. I remember when I was 11 or 12 we went to this part restaurant – part cabinet of curiosities – kind of tourist attraction place. In the back, there were carnival-type signs that read “Come see the Paiute Giant.” In this back room, there was a velvet rope around this sunken rectangular pit in the middle of this room. We were told to look down into the pit to see what was called the Paiute Giant but it was an excavated grave with a skeleton. It was real. You were looking at a real human being.

I remember looking into that pit and seeing cigarette butts and gum wrappers in and around the grave. There wasn’t anything protecting it. It was very hard to process. I do remember thinking that “I’m Paiute. That’s who I am. Is this somebody from my family?” and it was really confusing and upsetting. I didn’t know how to process it. Honestly, even now I don’t know how to process it. It brings up a lot of sad feelings but that was one of my most profound museum experiences to see one of my ancestors lie in the ground and people were literally throwing garbage at it. It’s really hard to explain the complicated feelings that it brought up in me.

How do these pivotal experiences impact your work at Ganondagan today?

It absolutely informs my work because I would be very upset to have a young Native person have to experience those things again. They’ve become, in my mind, the most important visitor just because of the personal connections that I have. I’m always imagining what we are doing and looking at it through that lens to make sure that kind of experience doesn’t happen to someone else.

I think about the young Native person coming here [to Ganondagan] to experience, to see, and to learn. I want them to come away with feelings of pride, feelings of empowerment. I want them to have a very different experience than what I got as a kid.

What are some of your biggest motivations in your work?

Someone once told me when you end up at this level at an organization you can be dragged down by what used to happen, or what you used to do, or how it’s normally done. You focus so much on maintaining what was, so you have a harder time visioning what could be or what should be.

I’ve been very conscious of trying to keep that list in my head and physically on my corkboard of things I want to accomplish and the ways in which Ganondagan can become something different and better. Those kinds of things excite me. Stepping outside yourself and looking at what you’re doing and knowing what you want to do. It’s important to always keep in mind what motivates you and what you really want to see happen and never forget them. You have to keep that visionary focus.

What are some of your goals for the Seneca Art & Culture Center and Ganondagan State Historic Site?

We’re a decidedly small museum. We have a small staff but we don’t act like a small museum. We act like a large museum and I feel like that’s the way we have to be.

We’re making connections in the International museum community and that’s a goal - to be recognized nationally and internationally and to be a leader in what we do. We’ve gained the confidence of Native people which is a huge goal. To have the confidence within the Native community to represent, and share stories, and art and history, that’s huge. We take that very seriously.

Can you describe a favorite day on the job?

The best day for me is when you don't even know what happened that day when you’re done. And then you think about all of the conversations you had, and all of the people who came here to share or to visit, and the connections you reestablished with people you work with, or with new people…those are some of the best days. You’ve built that energy all day long and you can just sit in a mental inner tube, let it push you down your river, enjoy what you've done, and what people have done together.

There are a lot of great days here, but we did a program a couple of years ago where we tried to bring the Bark Longhouse exhibit to life. We had people inside the Longhouse living, cooking, eating, and in historical dress. When we did this program we always made sure that we invited Native school kids so we had Tuscarora, Seneca, and Onondaga. One year, Tuscarora kids came and they were just young enough to still be pretty vocal and open. There was this one little kid - maybe nine or ten - who said “I want to live here” because they recognized that this was one of their ancestral homes and they were so swept up in the atmosphere we created. It was such a yes moment.

Do you have any key mentors or someone who has deeply influenced you? Is there any piece of advice that they gave you that you’ve held onto?

I’ve been very fortunate to have had lots of mentors but someone who stands out in my mind and kind of pushed me to a state of more professionalism was George Hamell. George worked at various museums and he ended his career at the Rochester Museum & Science Center as the Collections Manager for the Rock Foundation. He was one of the curators at the New York State Museum for a long time. He was very gentle with me but also pushed me towards what is considered a more museological ideology. In terms of well-cited research and constructing an exhibition from the ground up. He was very helpful and I could never repay him for that kind of mentorship. One thing he told me that I thought was very wise and maybe a little humorous was he said to me that “an exhibit is never completed, it is only installed.” There is always work to be done.

Michael Galban (left) with George Hamell in the archives at Rochester Museum & Science center

Michael Galban (left) with George Hamell in the archives at Rochester Museum & Science center